Herbst

Ausstellung

16.09.2024 – 19.11.2024

Art Space Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Nach Vereinbarung

Herbst

Ausstellung

16.09.2024 – 19.11.2024

Art Space Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Nach Vereinbarung

Hachiro Iizuka, Marcia Hafif and David Nash

Ausstellung

14.11.2023 – 22.12.2023

Art Space Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Nach Vereinbarung

Die Herbst-Accrochage vereint Arbeiten des japanischen Bildhauers und Installationskünstlers Hachiro Iizuka (1928–2008) und des englischen Bildhauers und Landartkünstlers David Nash (*1945) mit einer Arbeit der Minimalismus und Farbfeld-Künstlerin Marcia Hafif (1929–2018) aus New York. Die gemeinsame Schnittstelle der Arbeiten ist ihre Farbigkeit der drei Grundfarben.

Seit 1957 hat Hachiro Iizuka als Maler, Bildhauer und Installationskünstler in zahlreichen Ausstellungen in Japan, Amerika und Europa sein Werk vorgestellt. Er ist gehört zur japanischen „klassischen Moderne“.

Shigeo Chiba, der Kurator des Nationalmuseums für moderne Kunst, Tôkyô, bezeichnet Hachiro Iizuka in der Phase der Installationen ab 1979 als einen „Measurer of Space“, als einen der den Raum ermisst oder abgrenzt. Da viele seine Installationen auf die Wandfläche gebracht werden, setzt er das Drei-Dimensionale auf das Zwei-Dimensionale: die Wandfläche als notwendiger Faktor seiner Arbeiten. Sie steht im Spannungsverhältnis zu seinen oft rhythmisch über den Raum verteilten Arbeiten. Diese raumgliedernden Objekte um einen ruhenden Pol werden nicht einzeln, sondern in ihrer Gesamtheit erfasst.

Marcia Hafif gehört zu den frühesten Vertretern der so genannten radikalen oder analytischen Malerei. Sie hat die Mittel der Malerei auf die Textur und Ausdrucksqualität monochromer Farbflächen reduziert. Sie gehen allein von der Qualität und Materialität der Farbe aus. In der Ausstellugn besticht ihr quadratisches Bild „Indian Yellow“ mit der Intensität und Nuanciertheit der gelben Farbe.

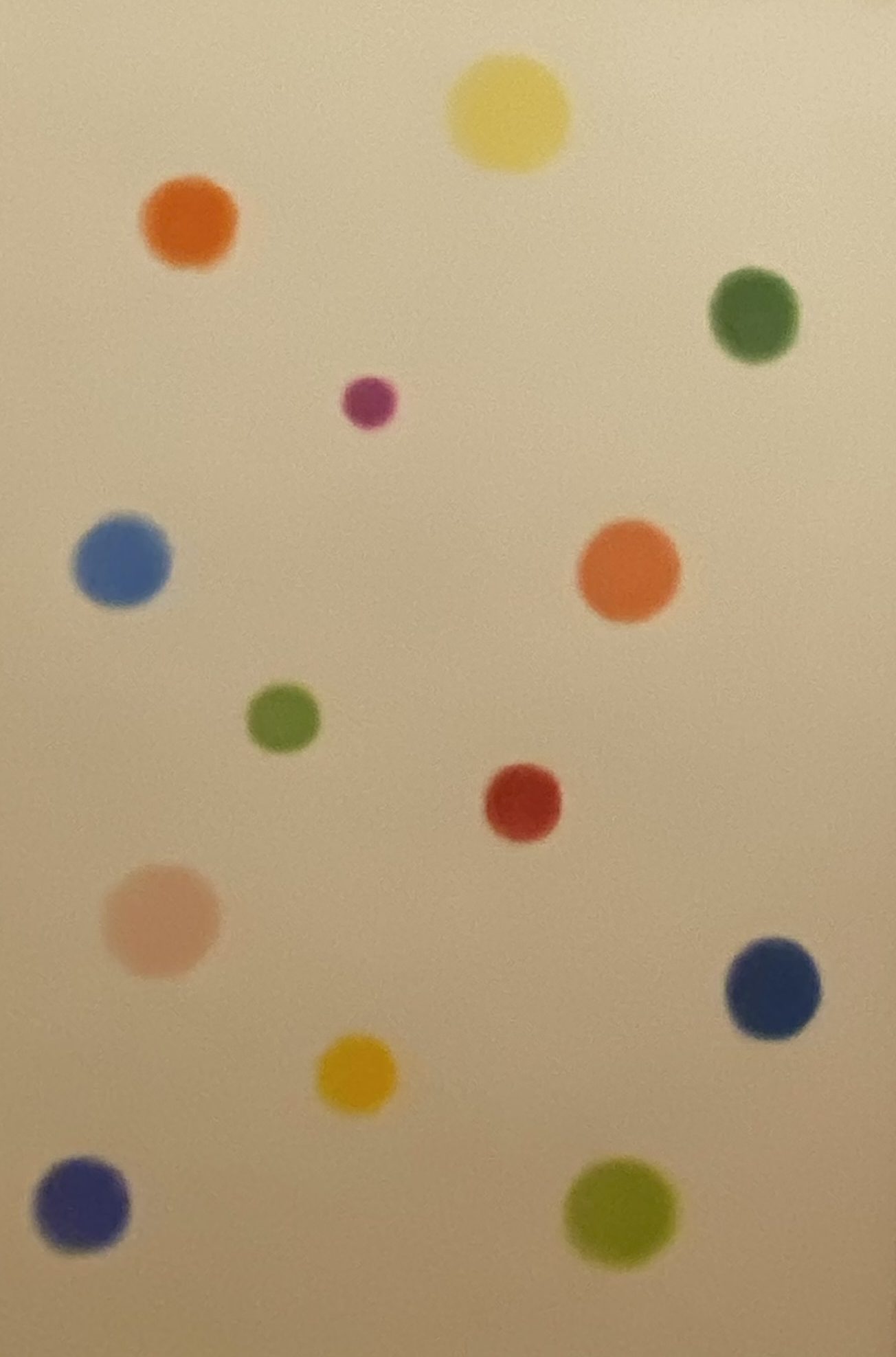

Der international renommierte Land Art-Künstler David Nash steht mit seinen skulpturalen Werken in einem ständigen Dialog mit der Natur, wobei die Lebendigkeit des Holzes eine große Rolle spielt. In der ausgestelltten Papierarbeithat er die Farben der Blumen in seinem Garten im Mai 2020 in ihrer Reihenfolge mit Kreisen aus Farbpigmenten wiedergegeben.

The autumn accrochage combines works by the Japanese sculptor and installation artist Hachiro Iizuka (1928–2008) and the English sculptor and land artist David Nash (*1945) with a work by the minimalist and colour field artist Marcia Hafif (1929–2018) from New York. The common interface of the works is their colourfulness of the three primary colours.

Since 1957, Hachiro Iizuka has presented his work as a painter, sculptor and installation artist in numerous exhibitions in Japan, America and Europe. He belongs to the Japanese „classical modernism“.

Shigeo Chiba, the curator of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tôkyô, describes Hachiro Iizuka as a „Measurer of Space“, as someone who measures or delimits space, during the phase of installations from 1979 onwards. As many of his installations are placed on the wall surface, he places the three-dimensional on the two-dimensional: the wall surface as a necessary factor in his works. It is in tension with his works, which are often rhythmically distributed across the room. These space-structuring objects around a stationary pole are not captured individually, but as a whole.

Marcia Hafif is one of the earliest representatives of so-called radical or analytical painting. She reduced the means of painting to the texture and expressive quality of monochrome colour surfaces. They are based solely on the quality and materiality of colour. In the exhibition, her square painting „Indian Yellow“ captivates with the intensity and nuance of the yellow colour.

With his sculptural works, the internationally renowned land art artist David Nash is in constant dialogue with nature, with the vitality of wood playing a major role. In the paper work on display, he has reproduced the colours of the flowers in his garden in May 2020 in their order using circles of coloured pigment.

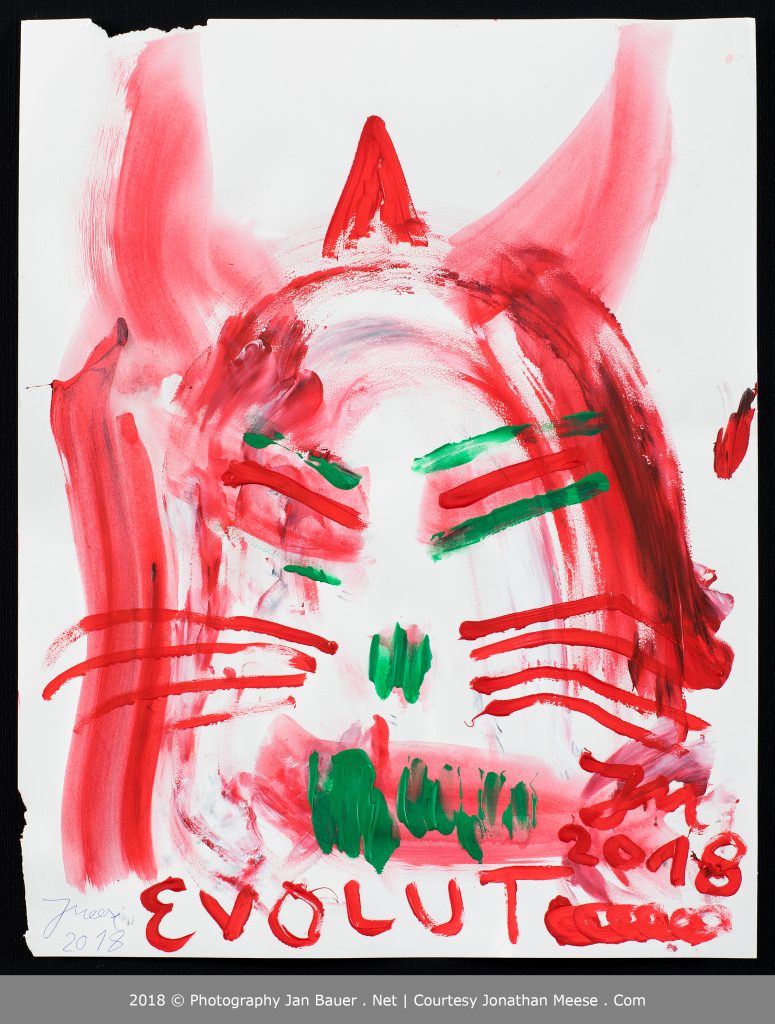

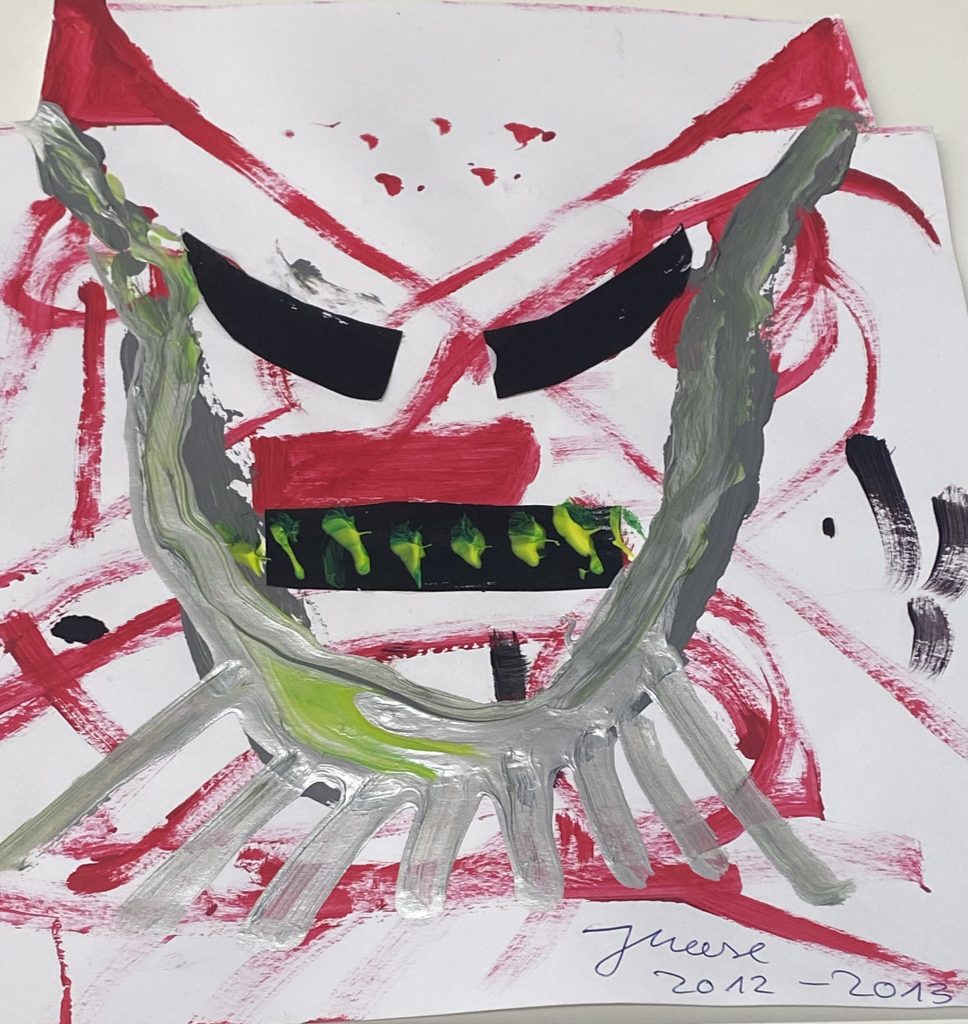

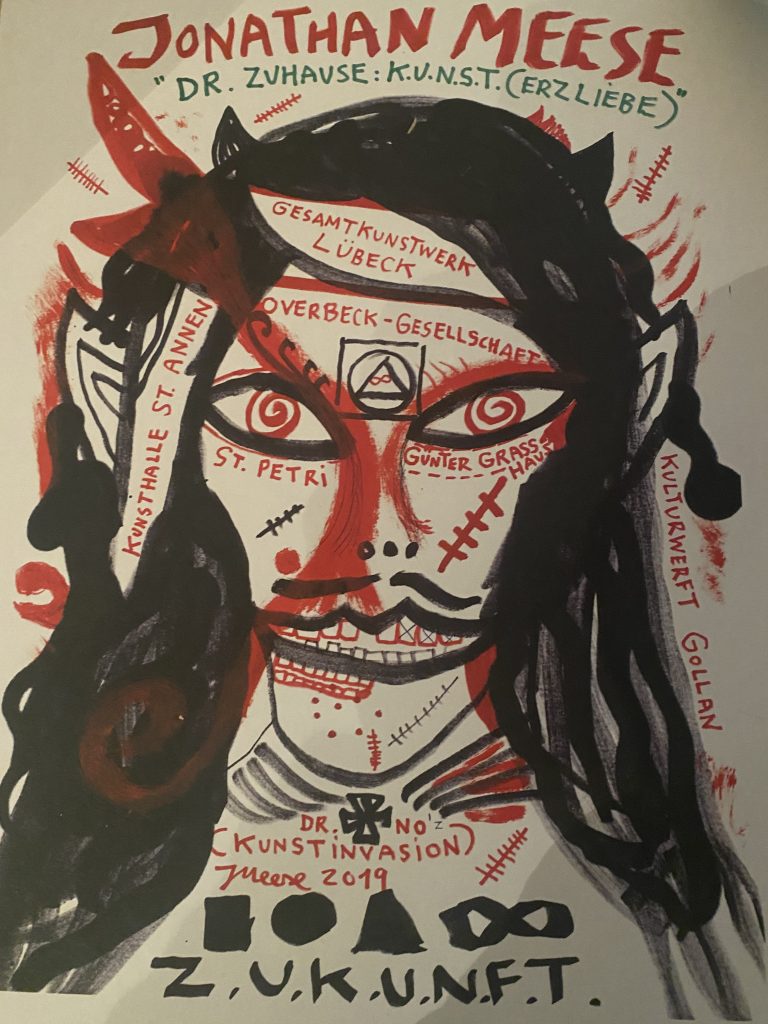

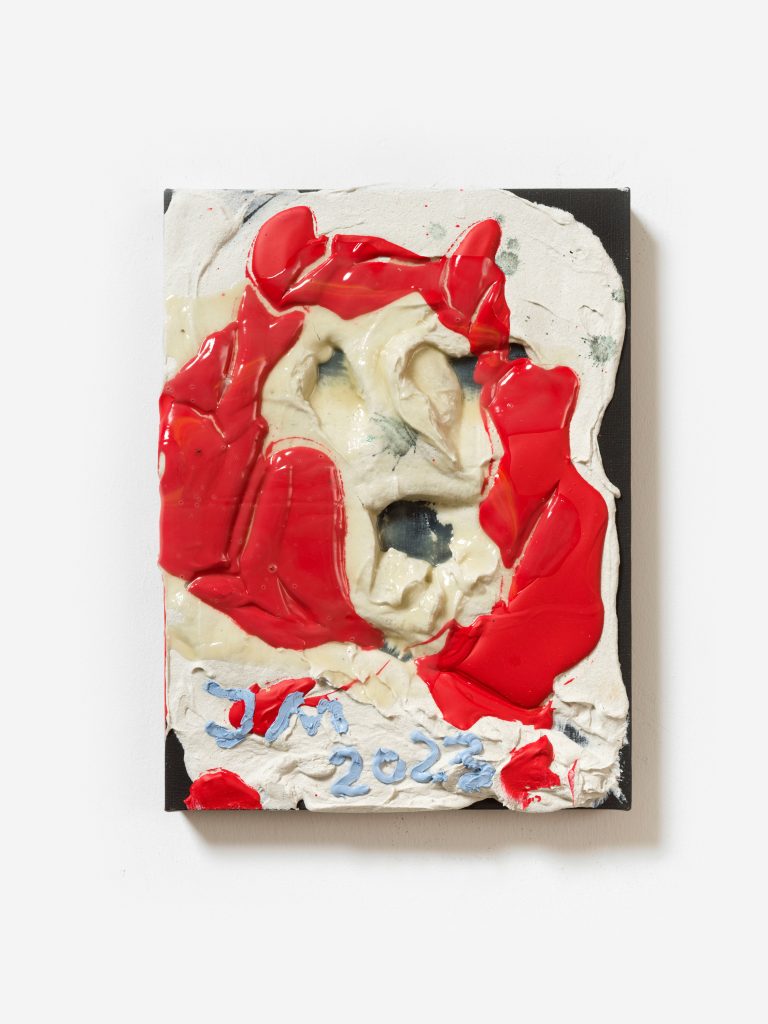

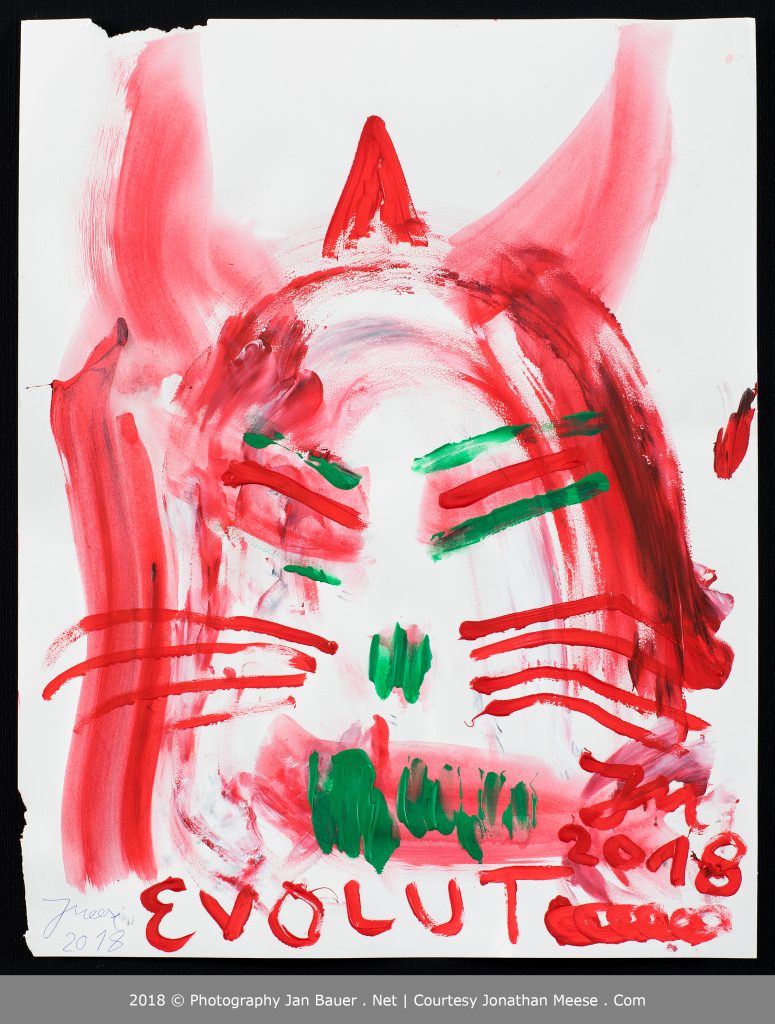

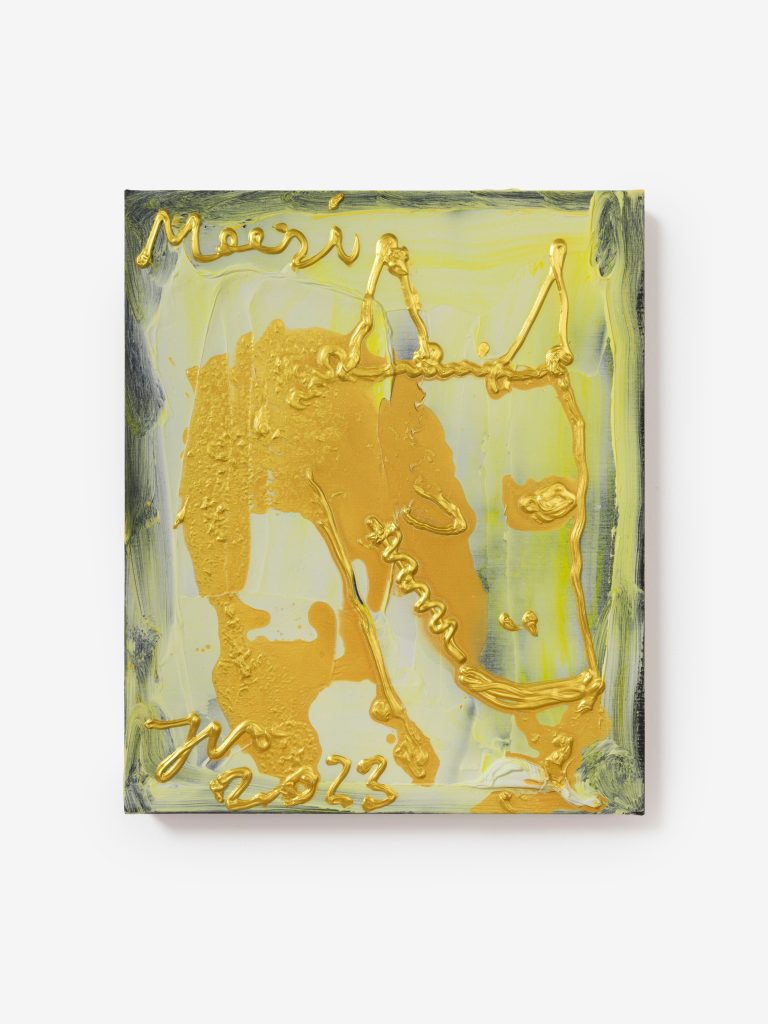

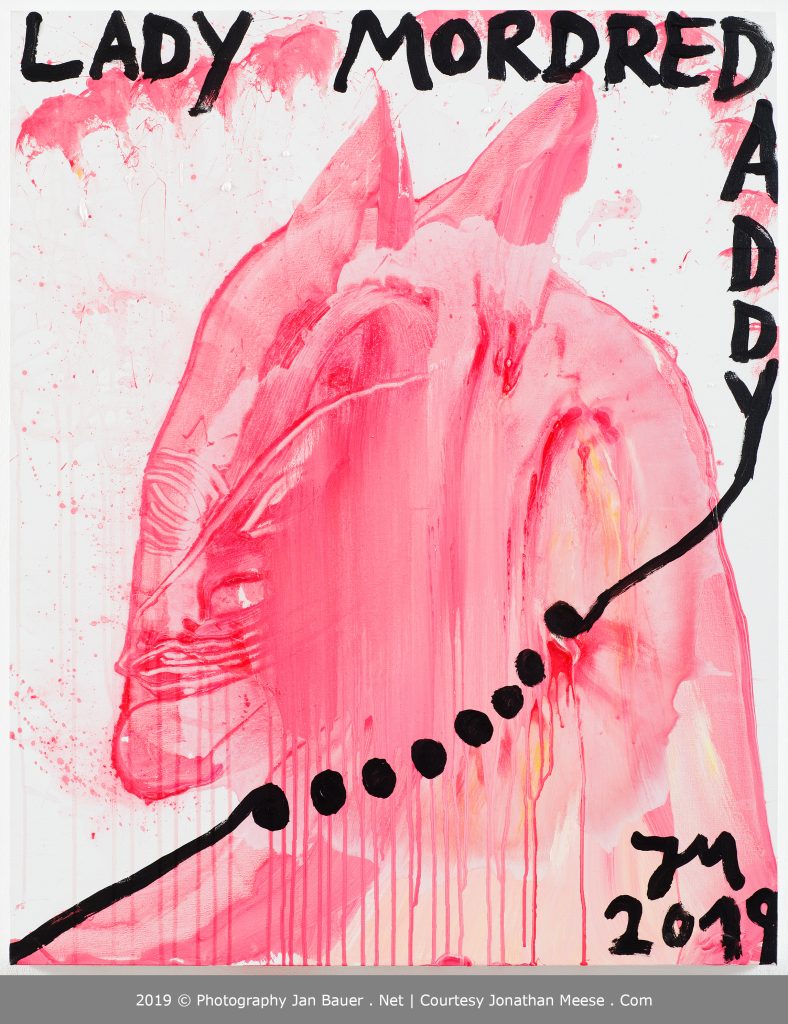

Zum TEUFEL MIT der KUNST

ONI WA SOTO

鬼わ外

Jonathan Meese im Zusammenspiel mit japanischen Teufeln

Eröffnung

13.09.2023 | 18–21 Uhr

Art Space Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Öffnungszeiten während der Berlin Art Week 2023

11–18 Uhr

Ausstellung

13.09.2023 – 25.10.2023

Art Space Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Nach Vereinbarung

Der charakteristische japanische Teufel (Oni) hat nicht nur buddhistische sondern auch chinesische Elemente in sich aufgenommen. Buddhistisch-stämmige Oni, die in der Hölle beheimatet sind, lassen sich leicht mit christlichen Teufeln vergleichen. Teufel werden als Menschen mit tierischen Merkmalen (Hörnen, Reißzähnen und Klauen) dargestellt: Oni wie christliche Teufel sind Gegenspieler der Menschen. In „Ecce Homo“ konstatiert Nietzsche über die Schöpfung: „war es Gott selber, der sich als Schlange am Ende seines Tagewerks unter den Baum der Erkenntnis legte: er erholte sich so davon, Gott zu sein… Er hatte Alles zu schön gemacht… Der Teufel ist bloß der Müßiggang Gottes an jedem siebten Tage…“. Wir brauchen den Teufel, um uns nicht zu langweilen. In der japanischen Sagen- und Ideenwelt gibt es im Gegensatz zum Westen eine Vielzahl verschiedener „böser“ Oni:

Shuten-Dôji

ist ein menschenfressender Oni, der in der Heian-Zeit (1185-794 n. Chr.) auftritt, und in erster Linie Frauen mit einem Biss verschlingt. Er haust auf dem Berg Oe nahe der Hauptstadt und raubt vorzugsweise adlige Frauen, die er versklavt, missbraucht und schließlich auffrisst. Erst dem tapferen Krieger Minamoto no Yorimitsu und seinen vier Vasallen gelingt es nach vielen Abenteuern Shuten-Dôji zur Strecke zu bringen. Die Geschichte hat eine verblüffende Ähnlichkeit mit dem griechischen Helden Odysseus und dem Zyklopen Polyphem. Shuten Dôji ist im Gegensatz zum Teufel nicht unsterblich.

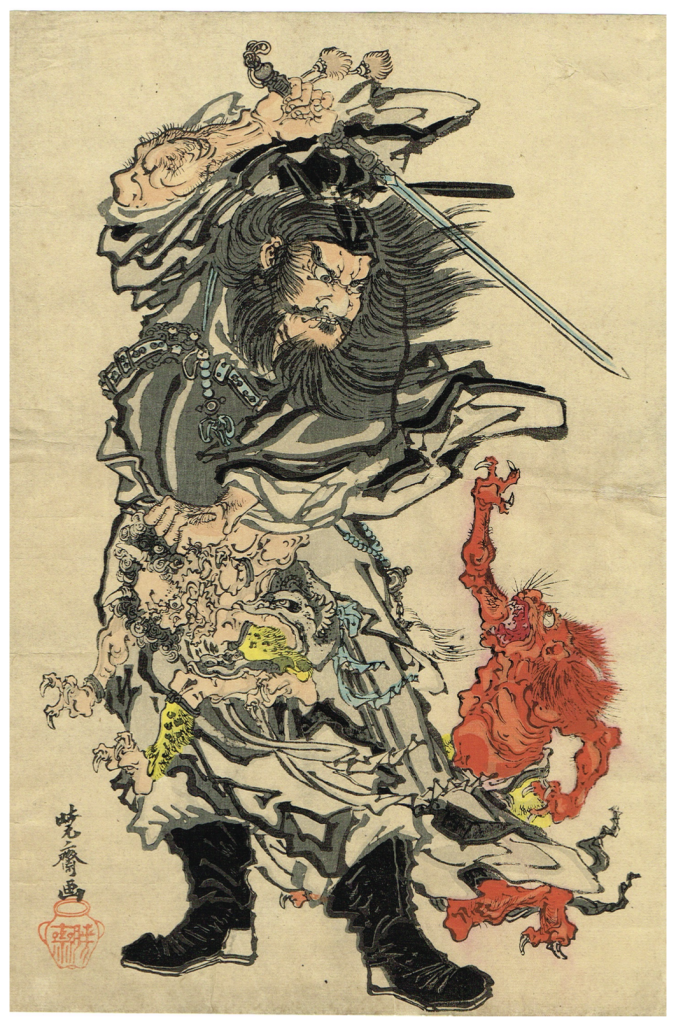

Shôki Dämonentöter

Shôki ist eine mächtige dunkel gekleidete Figur mit wildem Bart einer chinesischen Beamtenkappe und großen Stiefeln. In der einen Hand hält er einen Oni und in der anderen ein Schwert. Seine Bilder wurden als Talismane gegen Krankheiten eingesetzt.

Der Sage nach wurde Shoki (chin. Zhong Kui) in China ein Beamtenposten verweigert, weil er die Beamtenprüfung nicht bestanden hatte und weshalb er sich umbrachte und als Totengeist nicht zur Ruhe kam. Erst als der Kaiser ihn rehabilitierte übernahm der inzwischen versöhnte Geist Shokis das Amt als Dämonen- und Teufelsbezwinger für den Kaiser.

Oni als Tölpel

Seit dem 13. Jahrhundert gibt es in Japan auch Oni, die eher tölpelhaft als dämonisch sind, oft als buddhistische Pilger oder Musikanten verkleidet.

Oni wa soto – Teufelsaustreibung

Es gibt in Japan den Brauch, am 3. Februar (setsubun, letzter Tag des Winters) mit getrockneten Sojabohnen, die man in die Innenräume von Häusern wirft, Teufel und böse Gesister bzw. den Winter auszutreiben. Dabei ruft man „oni wa soto fuku wa uchi“ in der Hoffnung, dass die Teufel auf dem Boden ausrutschen.

Windgott – Donnergott

Es gibt gute Oni zur Bekämpfung von Seuchen und Oni-Masken/Oni-Darstellungen auf Dachschindeln

Berghexe Yamauba

Im Nô-Theater wird die Berghexe Yamauba mit einer hannya Maske dargestellt.

Neben den traditionellen Teufels (Oni)-Darstellungen in der japanischen Malerei, Holzschnittkunst und in der angewandten Kunst wird auch die Präsentation der Oni im zeitgenössischen, japanischen Leben eine Rolle spielen. Dabei vor allem in Form von Manga und Anime. Im zeitgenössischen Verständnis ist ein Oni ein Außerirdischer, ein Hybrid aus Erdbewohnern und einer anderen Spezies oder einfach eine andere Spezies auf der Erde aus der fernen Vergangenheit, der Zukunft oder, wenn er aus der Gegenwart kommt, aus einer anderen zeitlichen Dimension. Die Existenz eines Oni ist auch mit Spitzentechnologien wie Elektronik, Mechanik und Robotik verwoben. Im Cyberspace leben die Oni oft als Stadtbewohner mit den Menschen zusammen. Die Geopolitik mag sich ändern, aber der Oni ist immer noch ein entfremdeter „Anderer“. So wie die Themen der zeitgenössischen repräsentativen popkulturellen Medien sehr vielfältig sind, so ist auch die Darstellung der Oni sehr unterschiedlich.

Jonathan Meese wurde in Japan geboren. Der international renommierte Künstler arbeitet seit vielen Jahren zum Thema Teufel als Alter Ego in den Medien Malerei, Performance Film, Skulptur und Keramik. Für ihn ist die Kunst eine Notwendigkeit, um den Menschen in eine andere Denk- und Wahrnehmungsweise zu führen, die nicht von begrifflicher Sprache dominiert ist. Für ihn bedeutet Kunst die Form im Sinne einer universal gültigen Ordnung zu sehen. Kunst ist eine Weise, diese Ordnungen in eine Form zu bringen und erfahrbar zu machen. Jonathan Meeses Kunst führt in diesem Sinne einen Dialog mit den Oni der traditionellen japanischen Kunst in all ihren negativen, wilden und zerstörerischen Aspekten, sowie mit ihrer zeitgenössischen Präsentation in Anime und Manga, vor allem in ihrer Rolle als „Alien“.

Die Ausstellung zeichnet einen Spannungsbogen der traditionellen japanischen Kunst hin zur populären Gegenwart im Spiegel der Kunst Jonathan Meeses.

TO THE DEVIL WITH ART

ONI WA SOTO

鬼わ外

Jonathan Meese Interacting with Japanese Devils.

Opening

13.09.2023 | 6–9 pm

Art Space Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Opening Times during the Berlin Art Week 2023

11 am – 6 pm

Exhibition

13.09.2023 – 25.10.2023

Art Space Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

By Appointment

The characteristic Japanese devil (Oni) has incorporated not only Buddhist but also Chinese elements. Buddhist-derived Oni, who reside in hell, can easily be compared to Christian devils. Devils are depicted as humans with animal features (horns, fangs and claws): Oni, like Christian devils, are antagonists of humans. In „Ecce Homo“ Nietzsche states about creation: „He had made everything too beautiful… The devil is merely the idleness of God on every seventh day…“. We need the devil in order not to be bored.

In the Japanese world of legends and ideas, in contrast to the West, there is a multitude of different „evil“ Oni:

Shuten-Dôji

is a man-eating Oni who appears in the Heian period (1185-794 A.D.) and primarily devours women with one bite. He dwells on Mount Oe near the capital and prefers to rob noble women, whom he enslaves, abuses, and finally eats. Only the brave warrior Minamoto no Yorimitsu and his four vassals manage to hunt down Shuten-Dôji after many adventures. The story bears a striking resemblance to the Greek hero Odysseus and the Cyclops Polyphemus. Shuten-Dôji, unlike the devil, is not immortal.

Shôki Demon Slayer

Shôki is a powerful dark-clad figure with a wild beard of a Chinese official’s cap and big boots. He holds an Oni in one hand and a sword in the other. His images were used as talismans against illness. According to legend, Shôki (Chinese: Zhong Kui) was refused a civil service post in China because he had failed the civil service examination, which is why he committed suicide and never came to rest as a spirit of the dead. Only when the emperor rehabilitated him, the meanwhile reconciled spirit of Shoki took over the office of demon and devil vanquisher for the emperor.

Oni as dolts

Since the 13th century, there have also been Oni in Japan who are doltish rather than demonic, often disguised as Buddhist pilgrims or musicians.

Oni wa soto – exorcism of the devil

There is a custom in Japan on 3 February (setsubun, last day of winter), when dried soybeans are thrown into the interiors of houses to exorcise devils and evil spirits or the winter. They shout „oni wa soto fuku wa uchi“ in the hope that the devils will slip on the floor.

Wind god – Thunder god

There are good Oni for fighting epidemics and Oni masks / Oni representations on roof shingles.

Mountain witch Yamauba

In Noh theatre, the mountain witch Yamauba is depicted with a hannya mask.

In addition to the traditional depictions of devils (Oni) in Japanese painting, woodcarving and applied arts, the presentation of Oni in contemporary Japanese life will also play a role. Especially in the form of manga and anime. In contemporary understanding, an Oni is an alien, a hybrid of earthlings and another species, or simply another species on earth from the distant past, the future or, if from the present, from another temporal dimension. The existence of an Oni is also intertwined with cutting-edge technologies such as electronics, mechanics and robotics. In cyberspace, the Oni often live with humans as city dwellers. Geopolitics may be changing, but the Oni is still an alienated „other“. Just as the themes of contemporary representative pop cultural media are very diverse, so too is the representation of the Oni.

Jonathan Meese was born in Japan. The internationally renowned artist has been working for many years on the theme of the devil as alter ego in the media of painting, performance film, sculpture and ceramics. For him, art is a necessity to lead people into a different way of thinking and perceiving that is not dominated by conceptual language. For him, art means seeing form in terms of a universally valid order. Art is a way of bringing this order into a form and making it tangible. In this sense, Jonathan Meese’s art engages in a dialogue with the Oni of traditional Japanese art in all their negative, savage and destructive aspects, as well as with their contemporary presentation in anime and manga, especially in their role as „aliens“.

The exhibition draws an arc of tension from traditional Japanese art to the popular present in the mirror of Jonathan Meese’s art.

Fotos: Roman März und Claudia Delank

Visual Compositions without Sound

Makiko Nishikaze

Eröffnung

28.04.2023 | 18–20 Uhr

Kunstraum Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Artist Talk zwischen Makiko Nishikaze und Claudia Delank

29.04.2023 | 15 Uhr

Kunstraum Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Öffnungszeiten während des Gallery Weekend 2023

Fr. 28.04.2023 | 18–20 Uhr

Sa. 29.04.2023 | 11–18 Uhr

So. 30.04.2023 | 11–18 Uhr

Ausstellung

28.04.2023 – 02.06.2023

Kunstraum Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Nach Vereinbarung

Makiko Nishikaze: „Meine Arbeit mit Video, mit bewegten Bildern, führt zur Abstraktion: Durch Bildausschnitt, Montage und Konzentration auf die Bewegung wird der Ursprung des Objekts transformiert. Es kommt zu einer neuen Wahrnehmung der aufgenommenen Objekte. Sie werden abstrakt und offen für Assoziationen beim Betrachten. Ausgebildet bin ich als Musikerin. Inzwischen arbeite ich im Bereich Medienkunst. Ich finde, dass bewusstes Hören auch die Wahrnehmung durch die anderen Sinne intensivieren kann. Die Art, wie ich an meinen Videos arbeite, ist ähnlich, wie ich Musik komponiere. Die beiden haben die Gemeinsamkeit: die Zeit zu formen. Ich mache die Erfahrung, dass ich alle meine musikalischen Kenntnisse und Erfahrungen sehr gut für die Arbeit mit Video nutzen kann. Ich arbeite sorgsam an der Dramaturgie der Bilder – z.B. Reihenfolge, Verdichtung der Farbe, Tempo-Änderung, usw. – und die Ergebnisse sind für mich: Musik für die Augen. Ich nenne meine Videoarbeiten „experimentelle visuelle Komposition“ und meistens haben sie keinen Ton.“

Makiko Nishikaze: „My work with video, with moving images, leads to abstraction: the origin of the object is transformed through image detail, montage and concentration on the movement. There is a new perception of the recorded objects. They become abstract and open to associations when viewed.

I am trained as a musician. I now work in the field of media art. I find that conscious hearing can also intensify perception through the other senses. The way I work on my videos is similar to how I compose music. The two have one thing in common: shaping time. My experience is that I can use all my musical knowledge and experience very well for working with video. I work carefully on the dramaturgy of the images – e.g. order, concentration of colour, change of tempo, etc. – and the results for me are: music for the eyes. I call my video works „experimental visual composition“ and mostly they have no sound.“

At the Stillpoint of the Turning World

Performance-Video und Fotografie

Ausstellung

15.09.2022 – 11.11.2022

Kunstraum Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Nach Vereinbarung

Eröffnung

15.09.2022 | 18–20 Uhr

Kunstraum Claudia Delank | Bleibtreustr. 15–16, 10623 Berlin

Grußwort: Tokiko Kiyota, Stellvertretende Generalsekretärin, Japanisch-Deutsches Zentrum Berlin

U.A.w.g. bis 13.09.2022

Öffnungszeiten während der Berlin Art Week

Fr. 16.09.2022 | 12–18 Uhr

Sa. 17.09.2022 | 12–18 Uhr

So. 18.09.2022 | 12–18 Uhr

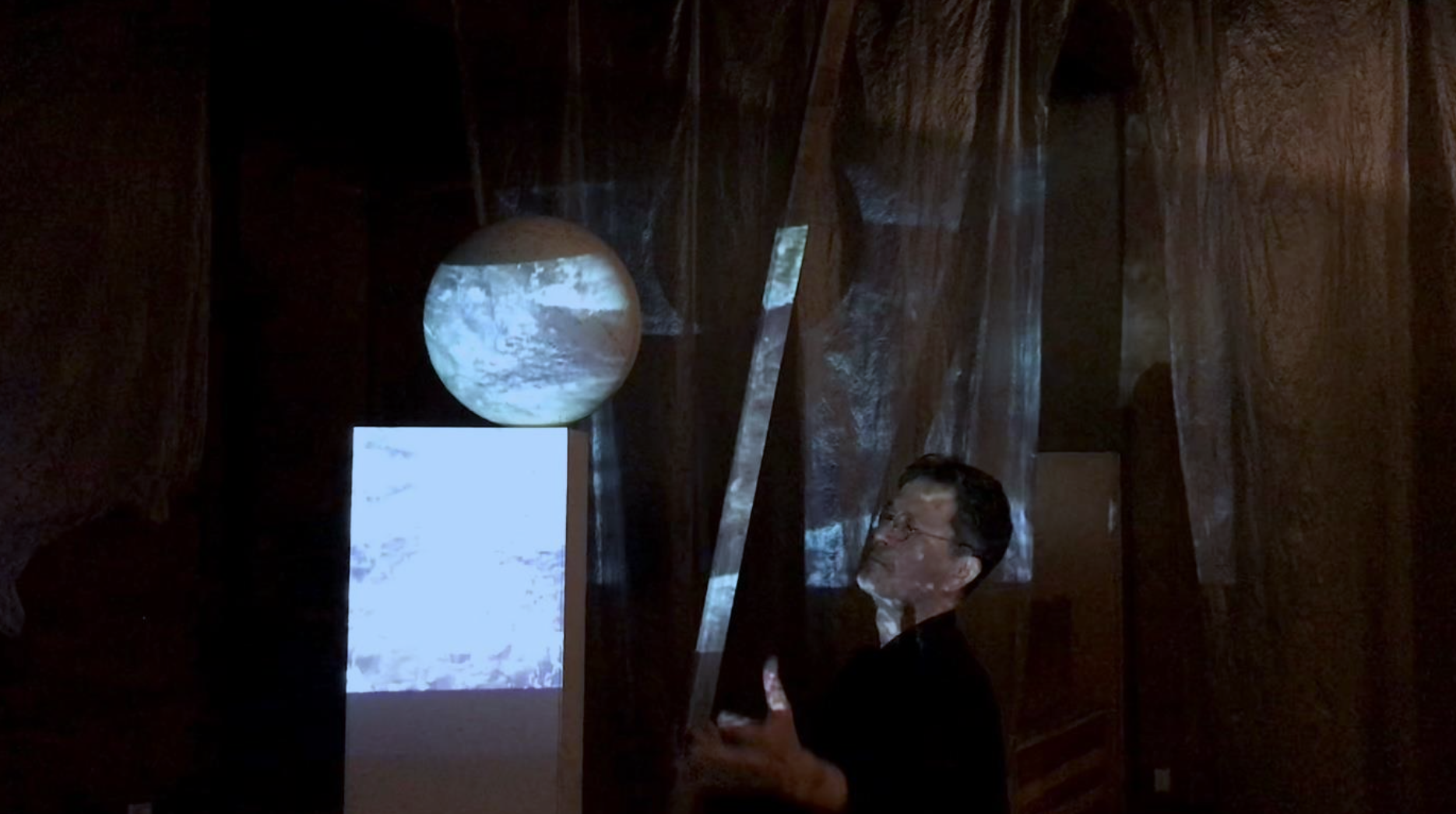

We are pleased to present Japanese artist Tokyo Maruyama’s solo exhibition “At the Stillpoint of the Turning World”.

His artistic work includes photography, installation and performance, which he has been producing since 1979 under the basic concept „Fieldworks in the City“. The starting point of the work is the city of Tokyo, which he depicts in his works as a place of transition and the intermediate world. He addresses the city as a living process. This is particularly evident in the photo series “Forms from Home” from the 1990s. A small wooden house acts as a reflection of the viewer. It symbolizes the artist’s spirit, absorbing and reflecting the environment at the same time. Behind the house, which acts as the center of the picture, there is a view of the Tokyo skyline, of a wasteland or of hidden alleys. Asymmetry and cropped objects play an important role in Maruyama’s photographs.

In his photo series “Simultaneous Positioning” from the 2000s, the chair plays the role of mediator between artist, object and viewer. It (the chair) stands between the artificial and the natural world and evokes the place of each individual in the world. An attribute is assigned to each chair, for example a pyramid made of salt as a sacrifice for the ancestors, a crystal ball as a symbol of the future, his father’s glasses as a biographical element or the hourglass as a symbol of the „memento mori“. In this series, the artist addresses “being”, which is subject to the endless flow of time and is therefore committed to transience, entirely to the Japanese philosophical attitude to life of “mono no aware” – awareness of the uniqueness of the moment, given its transience.

Matching the photo series “Simultaneous Positioning”, the video of the same name draws attention to the small area of the chair legs, which becomes the scene of the life and death of individual insects. The spectacle is filmed alternately in focus and out of focus to recall the Buddhist principle of rebirth. The video was made before the events of September 11, 2001. The rectangular chair legs become a symbol for the twin towers of the World Trade Center and the associated struggle for life and death.Other important elements of his performances are earth, a globe, chairs of different sizes and a glass eye, with which he expresses his positioning in the world.The artist has had numerous exhibitions in Japan, Europe and America since 1981.